Plea for Leopold and Loeb

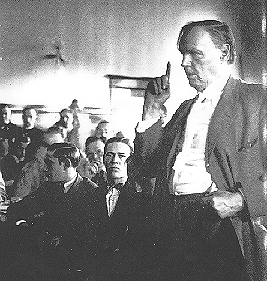

Clarence Darrow (Clarence Seward Darrow)

Historical Context

In the summer of 1924, Nathan Leopold Jr., 19, and Richard "Dickie" Loeb, 18, two wealthy, brilliant University of Chicago students, had confessed to the kidnapping and murder of 14-year-old Robert "Bobby" Franks in what they believed would be the "perfect crime." The case shocked the nation.

Leopold's father was a millionaire businessman and Loeb's family was equally prominent in Chicago's elite circles. Both boys were intellectual prodigies: Leopold spoke multiple languages and was headed to Harvard Law School, while Loeb was the youngest graduate in the University of Michigan's history. Yet they had committed a cold-blooded murder apparently for the thrill of it, motivated by their shared fascination with Nietzschean philosophy and the concept of the "superman" above conventional morality.

When their families hired Clarence Darrow, America's most famous defense attorney, the nation assumed he would plead them not guilty by reason of insanity. Instead, Darrow shocked everyone by entering a guilty plea, placing his clients' fate entirely in the hands of Judge John Caverly. This strategic move allowed Darrow to present evidence about the boys' mental state without the risk of a jury trial, where public outrage might ensure death sentences.

The case became a media circus, with reporters from around the world reporting. Public sentiment overwhelmingly favored execution as the crime seemed to embody fears about moral decay among the youth. Into this atmosphere stepped Darrow to deliver what would become his most famous courtroom performance: a 12-hour plea that challenged fundamental assumptions about justice, punishment, and human nature.

The Speech

[From the extensive closing argument delivered over three days, here are key excerpts:]

Now, your Honor, I have spoken about the war. I believed in it. I don't know whether I was crazy or not. Sometimes I think perhaps I was. I approved of it; I joined in the general cry of madness and despair. I urged men to fight. I was safe because I was too old to go. I was like the rest. What did they do? Right or wrong, justifiable or unjustifiable - which I need not discuss today - it changed the world. For four long years the civilized world was engaged in killing men. Christian against Christian, barbarian uniting with Christians to kill Christians; anything to kill. It was taught in every school, aye in the Sunday schools. The little children played at war. The toddling children on the street. Do you suppose this world has ever been the same since then? How long, your Honor, will it take for the world to get back the humane emotions that were slowly growing before the war? How long will it take the calloused hearts of men before the scars of hatred and cruelty shall be removed?

[...extensive middle portion discussing the boys' backgrounds, mental states, and the nature of their crime...]

I do not know how much salvage there is in these two boys. I hate to say it in their presence, but what is there to look forward to? I do not know but what your Honor would be merciful if you tied a rope around their necks and let them die; merciful to them, but not merciful to civilization, and not merciful to those who would be left behind. To spend the balance of their days in prison is mighty little to look forward to, if anything. Is it anything? They may have the hope that as the years roll around they might be released. I do not know. I do not know. I will be honest with this court as I have tried to be from the beginning. I know that these boys are not fit to be at large. I believe they will not be until they pass through the next stage of life, at forty-five or fifty. Whether they will then, I cannot tell. I am sure of this; that I will not be here to help them. So far as I am concerned, it is over.

I would not tell this court that I do not hope that some time, when life and age have changed their bodies, as they do, and have changed their emotions, as they do - that they may once more return to life. I would be the last person on earth to close the door of hope to any human being that lives, and least of all to my clients. But what have they to look forward to? Nothing. And I think here of the stanza of Housman:

Now hollow fires burn out to black, And lights are fluttering low: Square your shoulders, lift your pack And leave your friends and go. O never fear, lads, naught's to dread, Look not left nor right: In all the endless road you tread There's nothing but the night.

I care not, your Honor, whether the march begins at the gallows or when the gates of Joliet close upon them, there is nothing but the night, and that is little for any human being to expect.

[...continues with arguments about the boys' families, the effects of wealth, their psychological conditions, and broader themes about justice and mercy...]

Now, I must say a word more and then I will leave this with you where I should have left it long ago. None of us are unmindful of the public; courts are not, and juries are not. We placed our fate in the hands of a trained court, thinking that he would be more mindful and considerate than a jury. I cannot say how people feel. I have stood here for three months as one might stand at the ocean trying to sweep back the tide. I hope the seas are subsiding and the wind is falling, and I believe they are, but I wish to make no false pretense to this court. The easy thing and the popular thing to do is to hang my clients. I know it. Men and women who do not think will applaud. The cruel and thoughtless will approve. It will be easy today; but in Chicago, and reaching out over the length and breadth of the land, more and more fathers and mothers, the humane, the kind and the hopeful, who are gaining an understanding and asking questions not only about these poor boys, but about their own - these will join in no acclaim at the death of my clients. These would ask that the shedding of blood be stopped, and that the normal feelings of man resume their sway. And as the days and the months and the years go on, they will ask it more and more. But, your Honor, what they shall ask may not count. I know the easy way. I know your Honor stands between the future and the past. I know the future is with me, and what I stand for here; not merely for the lives of these two unfortunate lads, but for all boys and all girls; for all of the young, and as far as possible, for all of the old. I am pleading for life, understanding, charity, kindness, and the infinite mercy that considers all. I am pleading that we overcome cruelty with kindness and hatred with love. I know the future is on my side. Your Honor stands between the past and the future. You may hang these boys; you may hang them by the neck until they are dead. But in doing it you will turn your face toward the past. In doing it you are making it harder for every other boy who in ignorance and darkness must grope his way through the mazes which only childhood knows. In doing it you will make it harder for unborn children. You may save them and make it easier for every child that sometime may stand where these boys stand. You will make it easier for every human being with an aspiration and a vision and a hope and a fate. I am pleading for the future; I am pleading for a time when hatred and cruelty will not control the hearts of men. When we can learn by reason and judgment and understanding and faith that all life is worth saving, and that mercy is the highest attribute of man.

I feel that I should apologize for the length of time I have taken. This case may not be as important as I think it is, and I am sure I do not need to tell this court, or to tell my friends that I would fight just as hard for the poor as for the rich. If I should succeed in saving these boys' lives and do nothing for the progress of the law, I should feel sad, indeed. If I can succeed, my greatest reward and my greatest hope will be that I have done something for the tens of thousands of other boys, for the countless unfortunates who must tread the same road in blind childhood that these poor boys have trod - that I have done something to help human understanding, to temper justice with mercy, to overcome hate with love.

I was reading last night of the aspiration of the old Persian poet, Omar Khayyam. It appealed to me as the highest that I can vision. I wish it was in my heart, and I wish it was in the hearts of all.

So I be written in the Book of Love, I do not care about that Book above. Erase my name or write it as you will, So I be written in the Book of Love.

Read the Full Speech

Key Quotes

"I am pleading for life, understanding, charity, kindness, and the infinite mercy that considers all. I am pleading that we overcome cruelty with kindness and hatred with love."

Darrow's powerful summation of his central argument for mercy over vengeance

"Your Honor stands between the past and the future. You may hang these boys; you may hang them by the neck until they are dead. But in doing it you will turn your face toward the past."

Framing the judge's decision as a choice between progressive mercy and backward-looking revenge

"I have stood here for three months as one might stand at the ocean trying to sweep back the tide."

Darrow's vivid description of fighting against overwhelming public opinion

"Now hollow fires burn out to black, And lights are fluttering low... In all the endless road you tread There's nothing but the night."

Quoting Housman's poetry to describe the bleak future facing the defendants

"So I be written in the Book of Love, I do not care about that Book above. Erase my name or write it as you will, So I be written in the Book of Love."

Closing with Omar Khayyam's poetry to emphasize love and mercy over judgment

Rhetorical Mastery & Strategy

Darrow's closing argument represents a masterpiece of legal oratory that transcended typical courtroom advocacy to become a profound meditation on justice, mercy, and human nature. Delivered over twelve hours across three days, the speech demonstrated Darrow's genius for transforming a criminal trial into a broader examination of society's values.

The speech's structure reveals careful strategic planning. Darrow began by acknowledging the horrific nature of the crime, then systematically built his case for mitigation. He explored the boys' privileged but psychologically damaging backgrounds, their intellectual brilliance coupled with emotional underdevelopment, and their obsession with Nietzschean philosophy. Rather than deny their guilt, he reframed the question from "Did they do it?" to "Why did they do it, and what should we do with them?"

Darrow's rhetorical techniques were masterful. He employed vivid imagery: describing himself as "standing at the ocean trying to sweep back the tide" of public opinion. His use of poetry, particularly the Housman verse about "nothing but the night," provided emotional depth to legal arguments. He skillfully alternated between intimate appeals to Judge Caverly and broader philosophical statements about the nature of justice.

Perhaps most importantly, Darrow connected the specific case to universal themes. He linked the boys' violence to World War I, arguing that a society that had celebrated mass killing could hardly express surprise at individual violence. He challenged the deterrent value of capital punishment and questioned whether true justice could be achieved through vengeance. This approach transformed the trial from a local sensation into a national debate about crime, punishment, and social responsibility.

Historical Impact & Enduring Influence

Darrow's plea succeeded in its immediate goal: Judge Caverly sentenced Leopold and Loeb to life imprisonment plus 99 years, explicitly citing their youth as a mitigating factor. But the speech's impact extended beyond the courtroom as it became a foundational text in American criminal law and a landmark in the movement against capital punishment.

The arguments Darrow advanced would be echoed in Supreme Court decisions decades later. His emphasis on scientific understanding of criminal behavior helped legitimize the use of psychiatric evidence in legal proceedings.

The speech also demonstrated how skilled advocacy could shift public discourse on controversial issues. It helped establish the template for "trial of the century" media coverage that continues today. In the immediate aftermath, the case generated intense debate about justice and privilege. Critics argued that wealth had bought the defendants their lives, while supporters praised Darrow for elevating the discussion beyond vengeance to consider deeper questions about criminal responsibility.

Law schools have studied it for decades as an example of effective advocacy. Its themes of determinism versus free will, mercy versus justice, and individual responsibility versus social influence remain relevant to contemporary debates about criminal justice reform.

Leopold was paroled in 1958 after 34 years in prison and went on to do humanitarian work in Puerto Rico, arguably vindicating Darrow's faith in human redemption. Loeb was killed in prison in 1936. Their case continues to inspire books, plays, films, and legal scholarship, ensuring that Darrow's plea for mercy remains part of American cultural memory.

The speech also influenced the broader anti-capital punishment movement. Darrow's arguments about the ineffectiveness of deterrence and the finality of execution have been cited by abolitionists for nearly a century. As the United States continues to grapple with questions about criminal justice reform, his plea for "understanding, charity, kindness, and the infinite mercy that considers all" remains surprisingly modern and relevant.

About the Speaker

Clarence Seward Darrow (1857-1938) was America's most celebrated trial lawyer and one of the great orators of his era. Born in rural Ohio, he began his career as a small-town lawyer before moving to Chicago, where he gained fame defending labor leaders and social outcasts. By 1924, Darrow had already established himself as the country's premier criminal defense attorney and a passionate opponent of capital punishment.

Known for his rumpled appearance, folksy manner, and devastating cross-examinations, Darrow possessed an almost supernatural ability to connect with juries and judges. He combined deep legal knowledge with philosophical insights drawn from his reading of Darwin, Freud, and social reformers. His cases often became vehicles for larger debates about society, justice, and human nature.

When he accepted the Leopold and Loeb case, Darrow was 67 years old and at the height of his powers. He had never lost a client to the electric chair, and he viewed this case as perhaps his most important platform for arguments against capital punishment and for a more scientific understanding of criminal behavior.

View all speeches by Clarence Darrow