Speech to the Troops at Tilbury

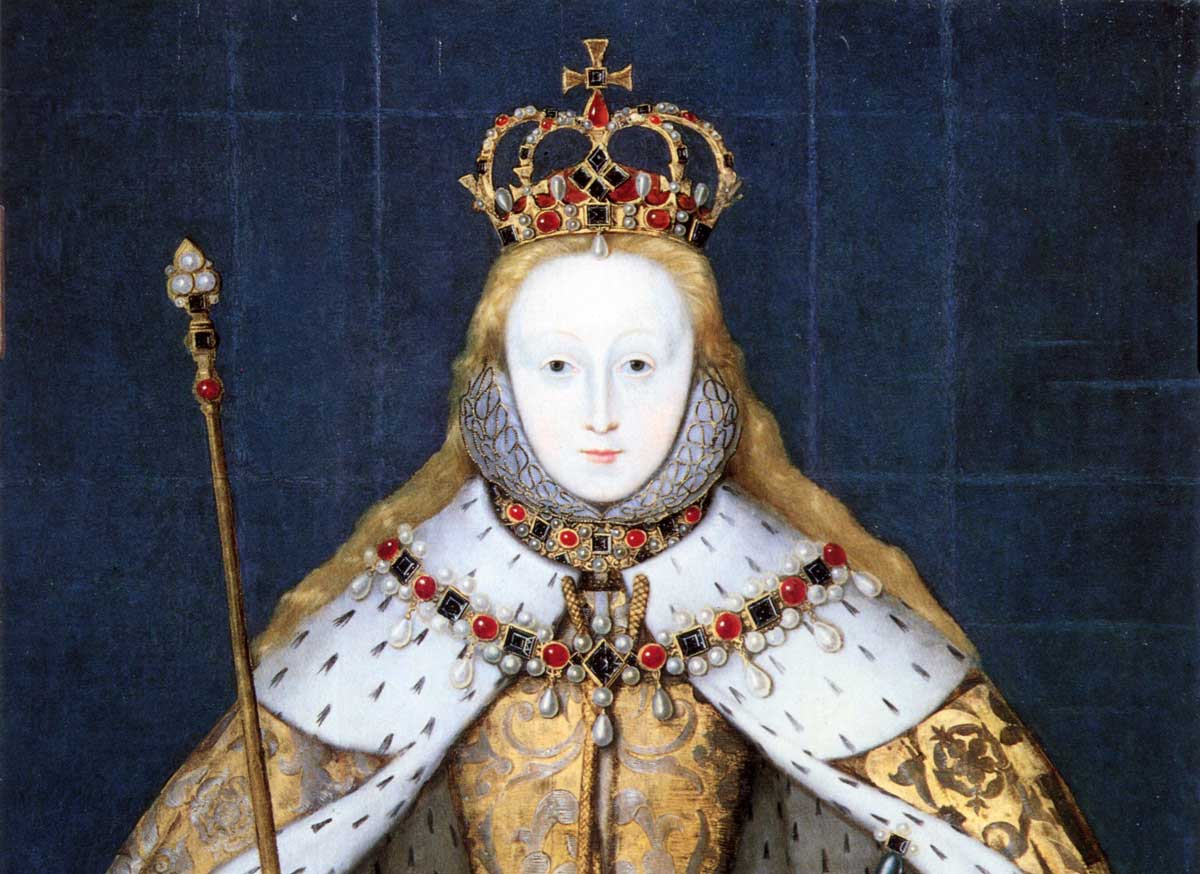

Elizabeth I (Elizabeth Tudor, Queen of England)

Historical Context

The summer of 1588 was England's greatest existential threat since the Norman Conquest. Philip II of Spain had assembled the Spanish Armada, the largest naval force ever seen, with 130 ships carrying 30,000 men, intent on overthrowing Protestant England and restoring Catholic rule. The "Enterprise of England," as the Spanish called it, represented the culmination of decades of religious and political conflict between Europe's two emerging superpowers.

Elizabeth I faced a crisis that would define not only her reign but England's future as an independent nation. Intelligence reports suggested that the Duke of Parma was massing 30,000 veteran troops in the Spanish Netherlands, ready to invade once the Armada secured the English Channel.

On the English side, the Royal Navy had fewer than 40 ships, and the hastily assembled land forces were largely untrained militia. At Tilbury, a strategic point on the Thames about twenty miles east of London, the queen's advisors had gathered approximately 20,000 troops as the last line of defense against invasion. These men represented England's final hope.

Elizabeth's councillors, including her chief minister Lord Burghley, had urged her to remain safely in London or retreat further inland. The risk of appearing before such a large armed assembly was considerable as assassination attempts were common, and the loyalty of hastily gathered troops could not be guaranteed. But Elizabeth, now 54 and at the height of her political powers, made the bold decision to personally address her forces. On August 9, 1588, she arrived at Tilbury dressed in white velvet with a silver breastplate, mounted on a grey gelding, to deliver what would become one of history's most famous royal speeches.

The Speech

My loving people,

We have been persuaded by some that are careful of our safety to take heed how we commit ourselves to armed multitudes, for fear of treachery. But I assure you, I do not desire to live to distrust my faithful and loving people.

Let tyrants fear. I have always so behaved myself that, under God, I have placed my chiefest strength and safeguard in the loyal hearts and good-will of my subjects; and therefore I am come amongst you, as you see, at this time, not for my recreation and disport, but being resolved, in the midst and heat of the battle, to live and die amongst you all; to lay down for my God, and for my kingdom, and my people, my honour and my blood, even in the dust.

I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm: to which rather than any dishonour shall grow by me, I myself will take up arms, I myself will be your general, judge, and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field.

I know already, for your forwardness you have deserved rewards and crowns; and We do assure you on a word of a prince, they shall be duly paid. In the mean time, my lieutenant general shall be in my stead, than whom never prince commanded a more noble or worthy subject; not doubting but by your obedience to my general, by your concord in the camp, and your valour in the field, we shall shortly have a famous victory over these enemies of my God, of my kingdom, and of my people.

Read the Full Speech

Audio & Video Resources

Key Quotes

"I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too."

Elizabeth's most famous declaration, transforming apparent weakness into strength through claims to masculine royal authority

"Let tyrants fear. I have always so behaved myself that, under God, I have placed my chiefest strength and safeguard in the loyal hearts and good-will of my subjects."

Contrasting her rule based on love and loyalty with tyrannical rule based on fear

"I am come amongst you, as you see, at this time, not for my recreation and disport, but being resolved, in the midst and heat of the battle, to live and die amongst you all."

Demonstrating her willingness to share danger with her troops rather than remain safely distant

"I myself will take up arms, I myself will be your general, judge, and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field."

Promise of personal military leadership and just recognition of service

Speech Analysis & Rhetorical Techniques

Elizabeth's Tilbury speech represents a masterpiece of royal oratory that transformed apparent weakness into strength. The address demonstrates her sophisticated understanding of rhetoric and her ability to navigate the complex challenge of female authority in a patriarchal military context.

The speech's opening establishes intimacy and trust through her address to "my loving people." By acknowledging that advisors feared for her safety among "armed multitudes," Elizabeth transforms a potential sign of royal vulnerability into evidence of her courage and faith in her subjects. In other words, she is acknowledging criticism only to transcend it. This rhetorical strategy runs throughout the speech.

Elizabeth's most famous lines: "the body of a weak and feeble woman" but "the heart and stomach of a king", represent a brilliant rhetorical maneuver. Rather than ignoring or denying contemporary beliefs about female weakness, she acknowledges them directly before claiming qualities of courage and authority. This approach allows her to appear both realistic and transcendent.

The speech's structure builds systematically from personal connection to martial resolve to practical assurance. Elizabeth begins by establishing her relationship with the troops, moves to defiant declarations about facing the enemy, and concludes with concrete promises about rewards and leadership. This progression takes listeners from emotional engagement through patriotic fervor to practical confidence.

Religious language permeates the address, reflecting the conflict's religious dimensions while positioning Elizabeth as God's chosen defender of Protestant England. References to "my God" and divine providence frame the struggle in cosmic terms, elevating a political conflict into a holy war where divine favor determines victory.

Historical Impact & Enduring Influence

Contemporary accounts describe the troops' enthusiastic response, and the address successfully achieved its primary goal of securing military loyalty and national unity at a moment of supreme crisis. Within days, news arrived that the English fleet had scattered the Spanish Armada, validating Elizabeth's confident predictions of victory.

It helped to crystallize emerging concepts of English exceptionalism and Protestant nationalism. The image of the virgin queen in armor, defying Catholic Europe, became central to English self-understanding for centuries.

The address also established important precedents for royal communication during national crises. Elizabeth's decision to appear personally before her troops, her use of direct, emotional language, and her willingness to share danger with her subjects influenced royal protocol for generations. Later monarchs, from Charles I to Elizabeth II, would draw on similar strategies when addressing the nation during wartime.

The speech has been quoted, adapted, and referenced countless times in literature, film, and political discourse. Shakespeare's history plays echo its themes, and it remains a touchstone for discussions about leadership, courage, and national identity. The famous "heart and stomach of a king" line has become one of the most quoted phrases in English history. Its combination of personal vulnerability and resolute leadership, its balance of humility and defiance, and its successful navigation of gender expectations offer lessons that transcend its historical moment.

The speech also contributed to the emergence of England as a major European power. By successfully rallying national resistance against Spanish hegemony, Elizabeth helped establish England's independence and set the stage for its later imperial expansion. The defeat of the Armada marked Spain's decline and England's rise as a naval power, fundamentally altering European balance.

About the Speaker

Elizabeth I (1533-1603) was one of England's most successful monarchs and one of history's most skilled royal orator. Born the daughter of Henry VIII and his second wife Anne Boleyn, Elizabeth's path to the throne was far from certain. She was declared illegitimate at age two when her mother was executed, and survived the reigns of her half-siblings Edward VI and Mary I before ascending to the throne in 1558 at age 25.

Elizabeth's education was extraordinary for a woman of her era. She was tutored by leading Renaissance humanists, she was fluent in French, Italian, Latin, and Greek, and well-versed in history, theology, and rhetoric. This classical education profoundly shaped her approach to public speaking, which combined scholarly sophistication with an intuitive understanding of political psychology.

When she delivered the Tilbury speech, Elizabeth had ruled for thirty years and had already demonstrated remarkable skill in using carefully crafted public addresses to navigate political crises. Her speeches to Parliament, her progresses through the countryside, and her carefully orchestrated public appearances had established her as a master of royal propaganda. At Tilbury, facing the greatest threat of her reign, she would deliver her most memorable performance.

View all speeches by Elizabeth I