Speech from the Dock

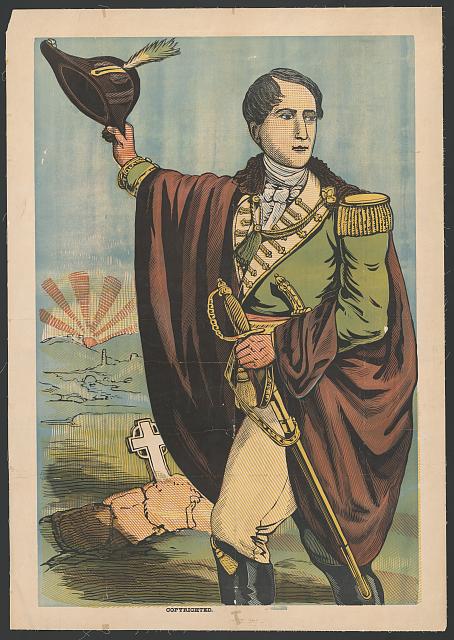

Robert Emmet

Historical Context

Ireland in 1803 was still reeling from the catastrophic failure of the 1798 Rebellion and the subsequent Act of Union that had dissolved the Irish Parliament and brought Ireland under direct British rule. At the time, Robert Emmet was a 25-year-old Protestant gentleman whose family had already sacrificed much for Irish independence and his brother Thomas was in exile in Paris for his role in the United Irishmen.

Robert Emmet's rebellion of July 23, 1803, was a desperate and poorly planned attempt to reignite the flame of Irish independence. The rising was intended to begin with the seizure of Dublin Castle, the seat of British power in Ireland, followed by coordinated uprisings throughout the country. Instead, it lasted barely a few hours and resulted in the deaths of several people, including Lord Chief Justice Kilwarden, who was brutally murdered by a mob.

By September 1803, Emmet had been captured, tried, and convicted of high treason. The evidence against him was overwhelming, and the British authorities were determined to make an example of this latest Irish rebel. The trial took place in the infamous Green Street Courthouse in Dublin, presided over by Lord Norbury, a notoriously harsh judge known for his cruelty and his determination to crush Irish resistance. Emmet was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging, drawing, and quartering, a sentence that was later commuted to simple hanging.

The Speech

What have I to say why sentence of death should not be pronounced on me, according to law? I have nothing to say which can alter your predetermination, not that it would become me to say with any view to the mitigation of that Sentence which you are here to pronounce, and by which I must abide. But I have that to say which interests me more than life, and which you have laboured, as was necessarily your office in the present circumstances of this oppressed country to destroy. I have much to say why my reputation should be rescued from the load of false accusation and calumny which has been heaped upon it. I do not imagine that, seated where you are, your minds can be so free from impurity as to receive the least impression from what I am about to utter. I have no hope that I can anchor my character in the breast of a court constituted and trammelled as this is. I only wish, and it is the utmost I expect. that your lordships may suffer it to float down your memories untainted by the foul breath of prejudice, until it finds some more hospitable harbour to shelter it from the rude storm by which it is at present buffeted.

Were I only to suffer death, after being adjudged guilty by your tribunal, I should bow in silence, meet the fate that awaits me without a murmur; but the sentence of the law which delivers my body to the executioner, will, through the ministry of the law, labour in its own vindication to consign my character to obloquy, for there must be guilt somewhere—whether in the sentence of the court, or in the catastrophes posterity must determine. A man in my situation, my lords, has not only to encounter the difficulties of fortune, and the force of power over minds which it has corrupted or subjugated, but the difficulties of established prejudice. The man dies, but his memory lives. That mine may not perish, that it may live in the respect of my countrymen, I seize upon this opportunity to vindicate myself from some of the charges alleged against me. When my spirit shall be wafted to a more friendly port—when my shade shall have joined the bands of those martyred heroes, who have shed their blood on the scaffold and in the field in defence of their country and of virtue, this is my hope—I wish that my memory and name may animate those who survive me, while I look down with complacency on the destruction of that perfidious government which upholds its domination by blasphemy of the Most High—which displays its power over man as over the beasts of the forest—which set man upon his brother, and lifts his hand, in the name of God, against the throat of his fellow who believes or doubts a little more or a little less than the government standard—a government which is steeled to barbarity by the cries of the orphans and the tears of the widows which it has made.

[Following Lord Norbury's interruption]

I appeal to the immaculate God—I swear by the Throne of Heaven, before which I must shortly appear—by the blood of the murdered patriots who have gone before me—that my conduct has been, through all this peril, and through all my purposes, governed only by the convictions which I have uttered, and by no other view than that of the emancipation of my country from the superinhuman oppression under which she has so long and too patiently travailed; and I confidently and assuredly hope that, wild and chimerical as it may appear, there is still union and strength in Ireland to accomplish this noblest enterprise.

[After further interruptions and exchanges with Lord Norbury]

I am charged with being an emissary of France. An emissary of France! And for what end? It is alleged that I wish to sell the independence of my country; and for what end? Was this the object of my ambition? And is this the mode by which a tribunal of justice reconciles contradictions? No; I am no emissary.

My ambition was to hold a place among the deliverers of my country—not in power, not in profit, but in the glory of the achievement. Sell my country's independence to France! And for what? A change of masters? No; but for my ambition. Oh, my country! Was it personal ambition that influenced me? Had it been the soul of my actions, could I not, by my education and fortune, by the rank and consideration of my family, have placed myself amongst the proudest of your oppressors? My country was my idol. To it I sacrificed every selfish, every endearing sentiment; and for it I now offer myself, O God! No, my lords; I acted as an Irishman, determined on delivering my country from the yoke of a foreign and unrelenting tyranny, and from the more galling yoke of a domestic faction, its joint partner and perpetrator in the patricide, whose reward is the ignominy of existing with an exterior of splendour and a consciousness of depravity.

[After describing his vision for Irish independence and his relationship with France]

Let no man dare, when I am dead, to charge me with dishonour; let no man attaint my memory by believing that I could have engaged in any cause but that of my country's liberty and independence; or that I could have become the pliant minion of power in the oppression and misery of my countrymen. The proclamation of the Provisional Government speaks for my views; no inference can be tortured from it to countenance barbarity or debasement at home, or subjection, humiliation, or treachery from abroad. I would not have submitted to a foreign oppressor, for the same reason that I would resist the domestic tyrant. In the dignity of freedom, I would have fought upon the threshold of my country, and its enemy should only enter by passing over my lifeless corpse.

[Following Lord Norbury's attack on his family]

If the spirits of the illustrious dead participate in the concerns and cares of those who were dear to them in this transitory life, O! ever dear and venerated shade of my departed father, look down with scrutiny upon the conduct of your suffering son, and see if I have, even for a moment, deviated from those principles of morality and patriotism which it was your care to instil into my youthful mind, and for which I am now about to offer up my life. My lords, you seem impatient for the sacrifice. The blood for which you thirst is not congealed by the artificial terrors which surround your victim—it circulates warmly and unruffled through the channels which God created for noble purposes, but which you are now bent to destroy, for purposes so grievous that they cry to heaven. Be yet patient! I have but a few words more to say. I am going to my cold and silent grave; my lamp of life is nearly extinguished; my race is run; the grave opens to receive me, and I sink into its bosom.

I have but one request to ask at my departure from this world; it is—THE CHARITY OF ITS SILENCE. Let no man write my epitaph; for as no man who knows my motives dare now vindicate them, let not prejudice or ignorance asperse them. Let them and me rest in obscurity and peace, and my name remain uninscribed, until other times and other men can do justice to my character. When my country takes her place among the nations of the earth, then, and not till then, let my epitaph be written. I have done.

Read the Full Speech

Key Quotes

"Let no man write my epitaph; for as no man who knows my motives dare now vindicate them, let not prejudice or ignorance asperse them. Let them and me rest in obscurity and peace, and my name remain uninscribed, until other times and other men can do justice to my character."

Emmet's most famous passage, requesting that judgment on his actions be delayed until Ireland achieves independence

"When my country takes her place among the nations of the earth, then, and not till then, let my epitaph be written."

The prophetic conclusion that became a rallying cry for Irish nationalism

"My country was my idol. To it I sacrificed every selfish, every endearing sentiment; and for it I now offer myself, O God!"

Emmet's passionate declaration of his devotion to Irish independence

"I acted as an Irishman, determined on delivering my country from the yoke of a foreign and unrelenting tyranny."

His defiant assertion of Irish nationalism and resistance to British rule

"The man dies, but his memory lives. That mine may not perish, that it may live in the respect of my countrymen, I seize upon this opportunity to vindicate myself."

Emmet's understanding of how martyrdom could serve the cause of Irish freedom

Speech Analysis

Robert Emmet's speech from the dock stands as one of the finest examples of oratory under the most extreme circumstances. A young man facing certain death transforming his final moments into a masterpiece of persuasive eloquence.

Emmet's rhetorical strategy was both bold and sophisticated. Rather than pleading for mercy or attempting to minimize his crimes, he used his final opportunity to speak as a platform for moral and political vindication. He shifted the focus from his failed rebellion to the larger struggle for Irish independence, positioning himself not as a criminal but as a patriot martyred by an illegitimate regime.

The speech's structure reveals careful preparation despite the dire circumstances. Emmet begins by acknowledging the court's predetermined judgment, then systematically addresses the charges against him, refuting accusations of being a French agent and asserting his pure motives. He builds to increasingly emotional peaks, culminating in his appeal to his dead father and his famous request for the "charity of silence."

Emmet's language combines classical rhetorical techniques with genuine passion. His metaphors are vivid and memorable and his reputation floating "down your memories untainted by the foul breath of prejudice" until it finds "some more hospitable harbour." His religious imagery and appeals to divine judgment elevate his cause above mere politics to moral principle. The repetitive structure of his denials ("No; I am no emissary") creates rhythmic emphasis that reinforces his points.

Perhaps most remarkably, Emmet demonstrates complete fearlessness in the face of death, using this moral authority to devastating effect against his judges. His calm acceptance of martyrdom, combined with his prophetic confidence in Ireland's eventual freedom, transforms what should have been his humiliation into his triumph.

Enduring Impact & Cultural Legacy

Robert Emmet's speech achieved something his rebellion could not: it kept the flame of Irish nationalism alive during one of its darkest periods.

The most famous line: "Let no man write my epitaph... When my country takes her place among the nations of the earth, then, and not till then, let my epitaph be written", became a rallying cry that echoed through Irish history. Leaders of every subsequent Irish uprising, from the Young Irelanders of 1848 to the Easter Rising of 1916, invoked Emmet's words and drew inspiration from his sacrifice.

The speech's literary qualities ensured its preservation and dissemination far beyond Ireland. Thomas Moore, Lord Byron, and other Romantic poets celebrated Emmet as a heroic figure, while his speech became a standard text in collections of great oratory.

In Irish-American communities, Emmet became a patron saint of the independence movement. His speech was recited at countless gatherings, and his image adorned homes and meeting halls throughout Irish America. The speech helped sustain Irish nationalist sentiment during the long decades when active resistance seemed impossible.

Beyond Ireland, the speech influenced anti-colonial movements worldwide. Leaders fighting for independence in other British colonies drew inspiration from Emmet's example of how eloquent defiance could transform military defeat into moral victory. The speech demonstrated how powerful oratory could transcend immediate circumstances to inspire future generations.

The speech also contributed to changing attitudes toward political prisoners and martyrdom. Emmet's dignified bearing and eloquent final statement helped establish the tradition of the "speech from the dock" as a form of political theater where defeated revolutionaries could claim moral victory over their oppressors.

Modern Ireland has struggled with how to commemorate Emmet, given the speech's association with violent nationalism. However, his call for an Ireland that would take "her place among the nations of the earth" resonates with contemporary Irish identity as a successful European democracy, suggesting that his ultimate vision has been fulfilled, if not in the way he originally imagined.

About the Speaker

Robert Emmet (1778-1803) was born into a respectable Protestant family in Dublin, the son of Dr. Robert Emmet, the state physician to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. Despite his family's comfortable position within the Protestant Ascendancy, young Robert was drawn to the ideals of the United Irishmen and their vision of an Ireland where Catholics and Protestants could unite in common cause against British rule.

Educated at Trinity College Dublin, Emmet was a brilliant student and a natural orator, serving as auditor of the College Historical Society, where he honed the speaking skills that would serve him so well in his final hour. However, his political activities forced him to leave Trinity in 1798 without taking his degree. He then traveled to France, where he met with Napoleon and other European leaders, seeking support for Irish independence.

When Emmet delivered his speech from the dock, he was just 25 years old, which made him younger than most of the judges who condemned him. Yet his words displayed a maturity, eloquence, and moral authority that transformed him from a failed revolutionary into one of Ireland's greatest martyrs. His youth, his Protestant background, his education, and his evident sincerity all combined to make his sacrifice particularly poignant and his words particularly powerful.

View all speeches by Robert Emmet